How to Lose Friends and Alienate People: The Importance of Understanding the Other Side if You Truly Want Peace - Part Two

This guest post is the second of a two-part series about the predominant cultural and historical narratives in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, intended to provide insight into frequently held mindsets on both sides. It should be read in conjunction with the first post, which can be found here. The author, Beirut and Beyond board member Steve Phillips, will be giving a presentation on these issues, the backstory of the land, and the evolution of this conflict at a Beirut and Beyond event on February 22nd. Come hear how the situation today is not a mystery, but has predictably resulted from a combination of factors, and join us in the discussion of a humanitarian response from a Christian perspective. All are welcome, regardless of faith.

It's almost inevitable that when trying to discuss this conflict objectively, you offend someone. But it's more likely that you'll offend almost everyone, because almost everyone significantly invested in it - whether physically or emotionally, from a distance - is affected by some degree of conflict neurosis, a social condition where people involved in a dispute develop irrational reflexes analogous to those seen in clinically neurotic individuals. Nowhere does this dynamic seem more active and destructive than in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Yet I remain a firm believer that unless you understand the other side from its own perspective, you’re doomed to fail in finding any common ground, let alone enough to resolve the strive. So while my first postintroduced some primary narratives on the Israeli side of this conflict, this post presents a similar summary of common Palestinian narratives. Because most Americans have limited familiarity with the historical background that drives these narratives, I’ve included that as well. What follows concerning the narratives below is not my own view of the situation, of the Palestinians, or the Israelis, but rather my observations about how they seem to view these things.

The name Palestine was used by Herodotusin the 5th century B.C. Between then and the end of the British Mandate in 1948, the land was occupied by the Israelites, Romans, Byzantines, several Arab caliphates, European Crusaders, and, for the last 300-plus years before the British, the Ottoman Empire. It’s got a messy history. In the late 1800s, the Zionist movement developed, promoting a global Jewish return to the ancestral Hebrew homeland. While Jewish communities were never wholly absent from the Holy Land after the fall of Jerusalem at Roman hands and start of the Jewish diaspora in 77 A.D., Zionism encouraged a wholesale migration of all Jews, with the goal of establishing a Jewish political state, and a steady immigration movement solidified.

As the Ottomans were defeated in World War One and the British took control of Palestine, the Zionist movement continued to grow. Under Ottoman rule, Palestine’s culture had been generally tolerant across religious lines, with Christian and Jewish minorities enjoying decent relations with the Muslim majority. But as tends to happen during any ethnic demographic shift, when the population continued to change, positive relations weakened and stresses arose between old residents and the new.

In addition to this, both the Arab and Jewish populations wanted independence from the British. Although neither group could successfully force the Crown’s hand, each mounted significant insurgencies, such that by the end of World War Two, England had had enough and, put simply, decided it wanted out and punted the problem to the United Nations. Without democratic representation from those who actually lived there, the UN voted to partition British Mandatory Palestine into two states, one for Jews and one for Arabs.

For those whose families had lived in Palestine for time out of mind, the partition plan began what they now see as a cascade of calamities. They tried to prevent the establishment of the State of Israel, but their capabilities had been severely crippled by losses sustained in their resistance against the British. Not only were they (along with forces from Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, and Syria) unable to stop Israel's formation, butthe West Bank fell to Jordanian control and Egypt occupied the Gaza Strip. Over 500,000 Palestinians were driven out ahead of advancing Jewish military forces. The UN partition plan called for 55% of the land to be allocated for a Jewish state. However, at the end of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Israel occupied 78% of the land. The newly formed nation subsequently and permanently precluded the refugees from returning to their homes or becoming citizens of the new State of Israel.

In 1967, after detecting troops massing across its border, Israel preemptively attacked several of its Arab neighbors. The Six-Day War ended with Israel thwarting the impending offensive, then wresting control of Gaza and the West Bank from Egypt and Jordan, as well as the militarily valuable Golan Heights from Syria. As with the 1948 war, it produced hundreds of thousands of refugees. Notwithstanding their origin and land ownership, these refugees, like those of 1948, have been prevented from returning to their homes ever since. Thus, while Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt each achieved independence from their colonial occupiers, the Palestinians went from Ottoman domination, to British rule, to subjugation by Jordan and Egypt, to the present situation, where they have no state and remain occupied by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

Lacking the diplomatic clout and military resources required to win independence and self-determination, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), led by Yasser Arafat, launched a campaign of attacks against civilian targets designed to bring the Palestinian cause into the global spotlight. The tactic indeed grabbed the world's attention, but, in the eyes of most Americans, concordantly tainted the Palestinians as a people. Although the PLO and its like saw themselves as freedom fighters, their most visible actions were, without question, attacks intentionally directed against civilians - and therefore plainly illegal under international law. Moreover, the campaign did not bring the Palestinians any closer to self-determination. Meanwhile, the UN and its member states that voted for the partition did nothing substantive to resolve the ongoing problem.

With their situation unchanged, in 1987, the Palestinians began a four-year grassroots uprising known as the first intifada (shaking off), employing strikes, road barricades, boycotts, tax refusals, and the throwing of stones and Molotov cocktails. A second intifada ran from 2000 to 2005, during which time the radical Islamist group Hamas, a rival to the now-somewhat-moderated Arafat, led a new style of terrorist campaign focused heavily on the use of suicide bombings. More recently, Hamas has focused on launching rockets from Gaza into Israel. As with other violent efforts, these actions have failed to produce Palestinian independence and served strengthened Israel's resolve to solidify its position, which it continues to do today as it expands its settlements in the occupied territory.

So as a result of this history, what conflict narratives permeate Palestinian culture today? First and foremost, there is a profoundly strong association with the land. For those who lived through the 1948 and 1967 wars, they will never forget: Palestine was the home of my parents, my grandparents, my great-grandparents, and my ancestors before them. It is where I am from, where I will always belong - with my people, in our place. And their children and grandchildren carry similar sentiments: Why are we forced to live in a refugee camp? For decades! Our family had land and prosperity in Palestine; here, we have nothing – we can’t own land, we are barred from getting jobs, and we can’t travel. All this because I was born a Palestinian?

The correlated sentiment that accompanies this is an insatiable sense of loss. When Israelis celebrate their Yom Ha’atzmaut (Independence Day) each spring, the Palestinians commemorate the Yohm an-Nakba (Day of the Catastrophe), recalling and grieving losing their lands and, for many, being forced into refugee camps where they and their descendants remain 68 years later.

This is perhaps a difficult thing for Americans to wrap their heads around. In the U.S., many saw the creation of Israel as a sensible idea because of the Jews' long diaspora and history of suffering in Europe – not just the Shoah (Holocaust), but centuries of discrimination and pogroms. However, most also overlooked the fact that Israel’s creation was possible only by appropriation of land where the Palestinians had resided since time out of mind. To my knowledge, the U.S. has never lost any of its sovereign territory. We have no national sense of loss of land, property, dignity, or self-determination – so it is perhaps hard for us to understand the depth of emotion associated with the Palestinian narrative, in which these things are so prominent.

From the Palestinians’ perspective, Western powers simply waltzed in and said, "Hey guys, you know those immigrants that you've been having a few problems getting along with? Look, you're going to give up half of your land to them. Yeah, I know there are way more of you than them, but they are going own about half the land now, including most of the more valuable parcels. Oh, also, you have to give them most of the water too." If you were a Zionist in 1948, the UN partition plan was a staggering success. But for Palestinians, it was the opposite - which is why they rejected it. Who are you to tell us we have to turn over our land to someone else? We've been here forever! And now, you’re telling me that anyone in the world can come here and become a citizen if they are Jewish – but we can’t go back to our homes and the lands our families have farmed for generations? Someone who has never been here can become a citizen, but I can never seemy home again? What about my rights?

I have often wondered how Americans would respond if they were told by the UN, Russia, China, and most of Latin America that the USA was going to be unilaterally partitioned, and Texas given to the Mexicans. How would those in Dallas and Houston react? Can you imagine anything other than a wholesale rejection of the idea by not only Texans, but all other Americans as well? Would Texans resist the partition? I’m not trying to draw an analogy here, but rather offering a fictional narrative that might invoke in us Americans sentiments similar to thosefelt by Palestinians.

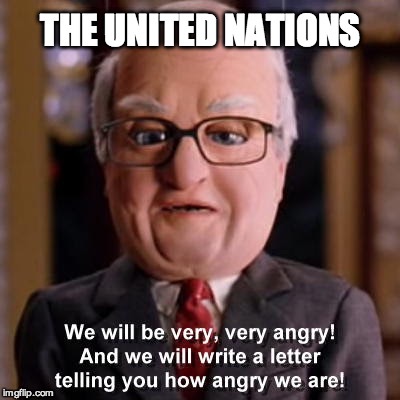

Added onto this sense of disenfranchisement is the knowledge that the UN, which sanctioned the Palestinians’ fate, has done nothing to ultimately address their losses. Millions of dollars have been thrown at the problem, but there is very little to show for it. The UN has condemned some Israeli treatment of the Palestinians, but the words have had no tangible effecton their day-to-day lives or their prospects for a better future.

Today, Palestinians that fled the 1948 and 1967 wars still cannot return home. If they could, most would find their homes destroyed or occupied by others with no intention of giving them up. They have received no compensation for the loss of their lands, homes, and businesses. With the exception of certain refugees who fled to Jordan or had the good fortune to realize immigration to the West, they have no citizenship – something that has impacts hard for Americans to grasp. As non-citizens in places like Lebanon and Jordan, refugees cannot own real estate and are barred from almost every profession. Very few landlords will rent to refugees. A third-generation refugee in Jordan with a college degree who competently speaks English cannot be hired at McDonald’s.

Gaza Palestinian Refugee Camp in Jarash, Jordan

This leaves generations of families in living in what most Americans would generously call a very difficult physical setting. In refugee camps, running water is limited, buildings are not heated in the winter, and public services are slight to non-existent. Over the course of 68 years, the UN has failed to remedy the problems it created with the partition. Though it has programs that have offered (meager) assistance, none of them have dealt with the ultimate problems – physical disenfranchisement, a lack of citizenship and its associated rights, and confinement to refugee camps, where the population grows, but community borders are fixed. Because of this, the message Palestinians have heard from the West – whether we intended it or not – has been this: You are not valued. You have no voice. You might as well not exist. Go away.

Gaza Palestinian Refugee Camp in Jarash, Jordan

Whatever politicians have said about the conflict or the humanitarian situation, the Palestinians’ personal experiences speak louder to them. Much louder. Whatever you do or say you are doing to help, nothing ever changes for us. We are still trapped and disenfranchised. Because of this perennial disenfranchisement and lack of voice, hopelessness plagues Palestinian communities – and fuels profound distrust. Because of that distrust, if there is ever to be a successful conversation about resolving the conflict, it has to start with an acknowledgement of these losses.

I think the narratives on both sides of the conflict are so strong that they are absolute firewalls against peace – unless they can be effectively met and properly addressed by the other side. The Israelis will never make peace with a Palestinian leader who praises terrorists or threatens (however impotently) to drive Jews into the sea. It doesn’t matter what his true reasons for such statements are or whether he’s merely posturing for a negotiating position. That kind of statement sets off every alarm in the Israeli national psyche and peace becomes a lost cause. Likewise, as long as the Palestinians feel robbed of their dignity, and that wound continues to be re-opened by Israeli policies, it will be impossible for their leaders to authoritatively negotiate for peace.

This is why the ongoing expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank complicates the peace process so much. Media reports often say that the settlements exacerbate the problems associated with drawing potential future borders, and that is true. But the more difficult to overcome damage is that each settlement is a fresh wound to the Palestinians that resounds their narrative: What we have can be taken at any time, our rights are subject to others’ whims, and our voices are meaningless to the world. We are losing the little we have left. This sentiment is reinforced by the ongoing Israeli presence in the West Bank, where Palestinian residents live with restricted movement between their homes and jobs, routine detention/denial at hundreds ofcheckpoints and road blockades, and other realities of military occupation. Similarly, the continuing Israeli blockade of the Gaza Strip perpetuates significant suffering of its civilian population, and that suffering has an even stronger effect.

For these same reasons, outbursts of anti-Semitism from those involved in the Palestinian BDS (boycott, divestment, and sanctions) movement are profoundly damaging to the peace process. The BDS movement presents itself as offering a nonviolent message not against Jews, but against specific Israeli policies affecting the Palestinians. But when Israeli and American Jews hear BDS activists shout bald-faced racial slurs or see one of them give a Nazi salute, any discussion concerning the Israeli government’s policies is done. The only message that is received is that here are more people who hate us because we’re Jews and wish we were dead. If the advocates of nonviolence are like this, are they really that much different from the terrorists?Time to circle the wagons. Those who said we couldn’t trust the Palestinians were right.

Just as the history of pogroms and the Shoah weigh heavy in the mind of Israeli Jews, the Nakba, the Six-Day War, and the ongoing occupation weigh heavy in the minds of Palestinians. And when it comes to finding peace, here’s the rub: It really doesn’t matter what you or I think. In the real world, like everyone else, Israelis and Palestinians are driven by their own narratives, not by your opinions or mine. Perhaps you think the Palestinians are wholly to blame for their own plight because they resisted the UN plan and some embraced terrorism. Perhaps you think the Israelis never had any right to a state and have committed widespread human rights violations. Regardless of where you stand, if you can’t step outside of that enough to address the other side’s most profound cultural fears and triggers, you’ve wasted your time. If you want to have a real conversation, you have to step into the other person’s shoes enough to defuse the reactions their cultural narrative will always trigger. In other words, if you don’t authentically acknowledge the other side’s narrative – as opposed to demeaning it or even demanding that they adopt yours – the result will be failure. And this conflict has had enough of that.